Shop so Orangutans don’t Drop

Laurel Neme

July 14, 2011

Next time you shop, consider orangutans. While U.S. grocery stores may be physically far from the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia, where these endangered primates live, the impact of supermarkets on orangutan survival is not so distant. About one in every ten products on your grocery store shelves contain palm oil. The problem is that unsustainable production, meaning “palm oil that’s developed at the expense of the remaining habitat of orangutans, is the single greatest threat to the survival of the species,” says Michelle Desilets, Executive Director of the Orangutan Land Trust.

About one in every ten products on your grocery store shelves contain palm oil. The problem is that unsustainable production, meaning “palm oil that’s developed at the expense of the remaining habitat of orangutans, is the single greatest threat to the survival of the species,” says Michelle Desilets, Executive Director of the Orangutan Land Trus

Palm oil is a key component in thousands of common household items, including cosmetics, processed food products like cookies and crackers, dairy products, soap and biofuels. It is widely used because its shelf life is longer than other vegetable oils and it is less costly and more efficient to grow.

The fruit itself contains about 50 percent oil and the trees produce year-round, meaning yields are significantly higher than for other oil-producing crops. For example, one acre produces about 1.6 tons of palm oil compared to 0.2 tons for soy or rapeseed (canola).

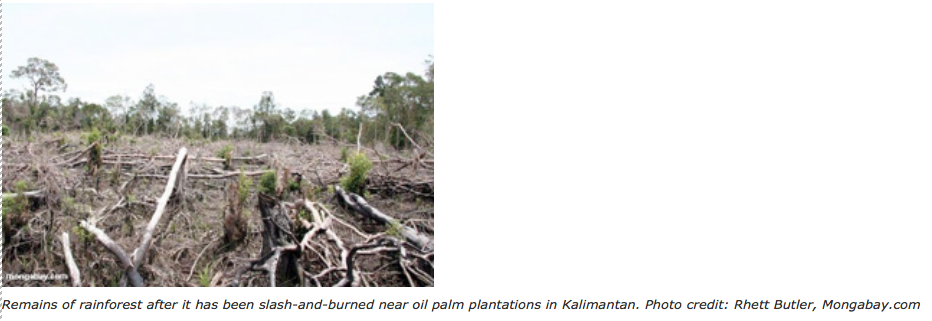

The vast majority of the world’s palm oil, about 75 percent, comes from industrial plantations in Indonesia and Malaysia, also home to the last wild orangutans. But it has become an ecological nightmare. That’s because huge tracts of tropical rainforest-about 20 square miles every day-are clearcut to make room for these monocultures. Typically, they are first logged of their valuable wood and then the remaining brush is burned. These unsustainable practices not only emit vast quantities of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, making Indonesia the third largest carbon emitter in the world, but it also pushes orangutans and other rare species into smaller and smaller fragments of forest.

“Without the forest, orangutans cannot exist,” Desilets says. Unlike chimpanzees and gorillas, orangutans spend their lives in the trees. They find their food there. They reproduce there. They nest there. With branches serving as their “highways” to travel from place to place, these red apes have little reason to come to the ground.

Orangutans are usually solitary by virtue of the distribution of food sources in their environment. Unless there is a mass fruiting season (which happens every decade or so), at any one time only certain trees provide fruit. With supplies insufficient for whole troops, orangutans usually disperse throughout the forest so that they can find enough to eat.

With their habitat chopped down, dwindling food supplies and more competition in the remaining areas prompt the orangutans to venture onto the newly planted plantations. There, they rip open the young palms to get at the soft, inner shoots, destroying the plants in the process. Plantation owners, angry over their losses, do almost anything to rid themselves of these agricultural pests. They even have put a $10 to $20 bounty on the heads of these creatures. The result: anywhere from 1,500 to 5,000 orangutans killed or sold into the pet trade each year.

The species can’t handle the loss. Orangutans in the wild are found only on two islands, Borneo and Sumatra, in Malaysia and Indonesia. Populations are in steep decline. The IUCN Red List estimates that about 50,000 Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) remain, half of the number from 60 years ago. The situation for Sumatran orangutans (Pongo abelii) is more critical, with about 7,300 animals in the wild, a decline of 80 percent over the past 75 years. Scientists warn these primates could become extinct in the wild in just four to 20 years.

Consumers can help orangutans by carefully considering their purchases. In the United States, demand for palm oil has tripled over the last five years. That’s contributed to the push of cultivation into the rainforests and the drive of orangutans out. Yet consumers can harness that same buying power for a more positive end by choosing products containing “greener” palm oil. That will create a market for and encourage more sustainable production.

Many companies have already responded. For example, Seventh Generation, the cleaning product company, has committed to buying sustainable palm kernel oil production credits for use across its entire line. Similarly, Unilever, the world’s largest palm oil buyer, has pledged to purchase sustainably produced palm oil. It even cancelled a contract with one company (PT Smart, part of the Sinar Mas group) after a Greenpeace report revealed violations of both Indonesian law and principles set out by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). The RSPO, which includes about 40 percent of palm oil suppliers as members, has developed eight principles and 39 criteria to limit the negative impacts of palm oil production.

The extra cost isn’t much. For American consumers, advocates estimate greener palm oil would cost about 40 cents per year to switch from conventional to certified sources. The catch is that palm oil is typically a hidden ingredient. Labels will list it as vegetable oil, with no further clarification. That makes it difficult to know which products even contain palm oil, let alone which ones use sustainably produced, certified varieties.

Until there is better labeling, the main option for shoppers is to do the research. Scorecards and other lists exist. Consumers just have to ask. By doing so, shoppers let producers know what they do want: certified, sustainable palm oil or its alternative. Orangutans can’t do it for you.