National Geographic: Rescued Circus Lions Airlifted to Safety in Africa (2)

Rescued Circus Lions Airlifted to Safety in Africa

Lions rescued from circuses in Peru and Colombia are set to arrive back home in Africa.

Forget the stagecoach and fairy godmother. When 33 lions rescued from circuses in Peru and Colombia touch down in South Africa on Saturday in a chartered cargo plane, their change in fortune will have come about thanks to Jan Creamer and Tim Phillips, real-life animal saviors with the U.K.-based nonprofit Animal Defenders International (ADI).

None of the lions can be released into the wild. As circus performers, they’ve had their claws removed and teeth smashed by their handlers, making it impossible to fend for themselves or catch prey.

But on Saturday they’ll have the next best thing as they set foot in pristine South African bush at the Emoya Big Cat Sanctuary, complete with drinking pools, platforms, and toys.

The effort took shape after an investigation by ADI into animal abuse in Latin America’s circuses and a multi-year, multi-country campaign to “Stop Circus Suffering” inspired regulatory changes across the region. Peru banned wild animal acts in 2012 and sought ADI’s help to enforce the new law. ADI called it Operation Spirit of Freedom.

Thirty-two countries around the world have nationwide restrictions on performing animals in traveling circuses. Four more (including the United States) are considering similar laws.

In 2009, ADI had helped Bolivia implement its ban in a first-of-its-kind undertaking called Operation Lion Ark that rescued and re-homed 29 lions and other animals.

“Peruvian wildlife officials hadn’t had a piece of legislation like this before that allowed them to go in and seize illegal animals,” Creamer explains. “In a lot of countries, that’s a problem. How do you move them? Where do you put them? Especially when you have a lot of large, dangerous animals.”

Expanding Operation

Based on their initial inventory, ADI expected Operation Spirit of Freedom would rescue 21 lions and 12 other animals. Creamer and Phillips figured it would be similar to their experience in Bolivia. But it quickly expanded into the largest such rescue operation to date.

“We thought we could do the operation in four months,” Phillips recalls. In the end it took more than 18 months and involved 33 lions in two countries, three bears, one tiger, one mountain lion, and a host of other animals including monkeys, kinkajous, coatimundis, and macaws. (The tiger, Hoover, rescued in Peru from Circo Africano, landed in Florida last Saturday and is now ensconced in a big cat sanctuary near Tampa.)

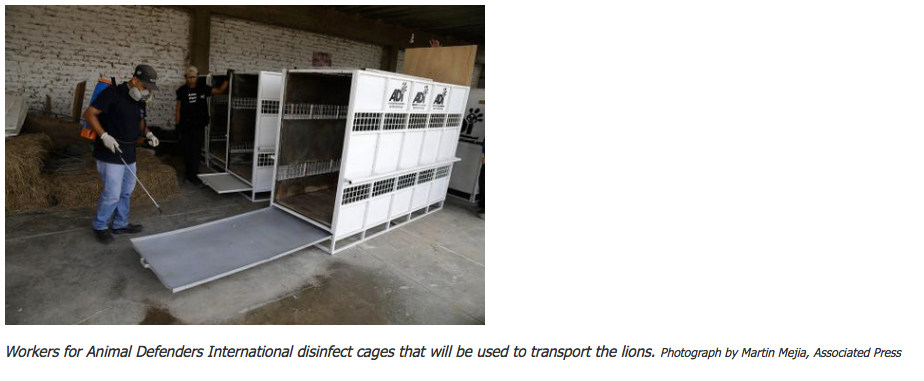

Workers for Animal Defenders International disinfect cages that will be used to transport the lions. Photograph by Martin Mejia, Associated Press

Raids on the circuses often turned nasty. Owners hid the animals, tried to negotiate, violently resisted, and even threatened to release them onto the streets. Often, the police had to bring in reinforcements.

Sometimes, ADI teams discovered more animals than anticipated.

“When we go into a rescue, we do accounts of what animals and what species are in the circuses,” Creamer says. “But sometimes you don’t know all the animals you have. Maybe the circus purchased a new animal, or they kept an animal somewhere else, so it’s not in our census. We have to be prepared for that.”

The operation expanded because authorities also wanted ADI to help them confiscate and care for animals in the illegal trade.

“They had a lot of locations where they wanted to seize animals that had been stolen from the wild and had been trafficked,” Creamer says. “Some had been passed to circuses, and some were on their way to private ownership as pets. We helped them deal with those seizures too, and that contributed to the growth in the numbers of animals.”

Public Support

Being on the ground for so long brought the issue of animal welfare to the forefront of the Peruvian public’s attention and rallied support for the confiscations.

The number of eyes and ears on the ground expanded as people looked out for circuses that had gone underground in an attempt to avoid seizure of their animals. Even in the remotest locations, villagers notified ADI when they spotted a “missing” circus. Indeed, that’s what led to the mission’s final rescues—of Hoover and Mufasa the mountain lion and Condorita the condor from Circo Koreander—outside two small villages in northern Peru last April.

“We wouldn’t have found these circuses but for people in Peru who got behind this mission,” Phillips says.

Some of the incidents exposed by ADI, such as the extreme abuse of Cholita the spectacled bear—who was completely hairless with her paws mangled and teeth smashed when she was rescued, in March 2015—inspired new laws in Peru against animal cruelty.

Yet that’s only part of the legacy.

“We’re working with local authorities, encouraging them, showing them that rescuing these animals is a popular thing with the public,” Phillips says.

The idea, he says, is to strangle demand for wild animals being pulled from the rain forest and show that there’s nowhere for dealers to hide.

“We feel strongly that if we do an operation to empty an industry of suffering animals, it would be unconscionable to leave any behind,” Creamer adds.

And, if they had, Phillips warns, “we would have seen it creeping back. We’ve shown that ADI will track you down and remove those animals. It sends a clear message. There’s no incentive to have those animals—they’ll be confiscated.”

Going Home

The 33 lions airlifted this week will be the last of the 108 rescued animals to settle into their new home. Where possible, the animals are being rehabilitated for return to the wild. Already, a tortoise and a military macaw named James have been freed.

But that’s not an option for many of the animals—those habituated to humans, permanently disabled, or in poor health—so ADI has done the next best thing and placed them in sanctuaries. Pepe the spider monkey, for instance, who spent his life alone and chained up, is now part of a troop of six living in the Peruvian Amazon. Similarly, Cholita and two other rescued spectacled bears are at Peru’s Taricaya Ecological Reserve.

“We fenced off a piece of rain forest on land owned by a sanctuary,” Creamer says. “We build enclosures for the animals and pay for their lifetime care. It’s protected, but it’s their natural habitat, with trees and vines and shrubs.”

The lions too will be going to their natural habitat—in Africa. “It’s different than booking a regular charter,” says Creamer, understating the logistics involved.

The process begins Friday with the transfer of nine lions voluntarily surrendered by a Colombian circus more than a year ago from a government rescue center in northern Colombia to the regional airport at Bucaramanga. From there, they’ll fly in a small cargo plane to Bogota, where in the wee hours of Saturday morning they’ll be transferred to a large MD11F cargo jet bound for Lima to pick up the 24 Peruvian lions.

The lions will be in separate crates for the more than 14-hour flight, positioned strategically so that each animal is within sight of a familiar face. Creamer and Phillips will travel with them in the cargo hold to calm them and make sure everything goes smoothly. They’ll then be trucked from Johannesburg to Emoya Big Cat Sanctuary, in the small town of Vaalwater, in Limpopo Province.

Not quite the wave of a wand and a “bibbidi-bobbidi-boo,” but by sundown the big cats will be exploring their large natural enclosures in the African bush.

“It’s the perfect ending,” Creamer says. “These lions have endured hell on Earth, and now they’re heading home to paradise.”

Laurel Neme is a freelance writer and author of Animal Investigators: How the World’s First Wildlife Forensics Lab Is Solving Crimes and Saving Endangered Species and Orangutan Houdini. Follow her on Twitter and Facebook.