National Geographic: How the International Trade in Geckos Is a Scam (2)

How the International Trade in Geckos Is a Scam

The coauthor of a new report says low-profile species are often hit hardest by illegal and unsustainable trade.

PUBLISHED

Tokay geckos are the world’s second largest species of gecko, with males reaching lengths of up to 15 inches (38 centimeters). Photograph by blickwinkel/Alamy Stock Photo.

For many species threatened by the illegal wildlife trafficking, such as rhinos, elephants, tigers, and bears, debates persist as to whether a legal trade in their parts and products can reduce smuggling.

But increasing evidence suggests that a legal trade instead acts as a conduit for the illegal trade. For instance, recent studies showed that Hong Kong’s domestic ivory sales provided cover for illegal stocks. Now, a new report by TRAFFIC, a wildlife monitoring NGO, on captive breeding of Tokay geckos in Indonesia suggests the same holds true for captive breeding.

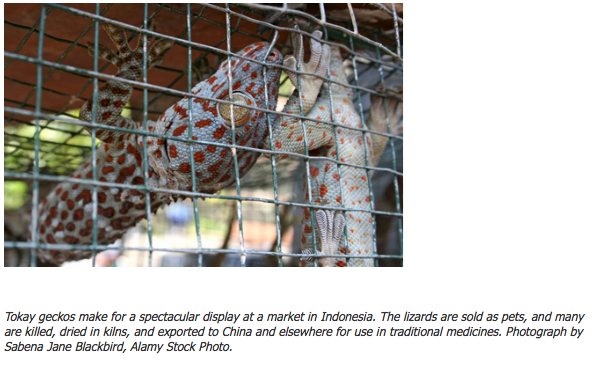

Tokay geckos are nocturnal lizards that live in Southeast Asia. While there is some demand for them as pets, the real demand is for their use as traditional Asian medicines—everything from an aphrodisiac and energy drink to treatments for diabetes, cancer, and HIV/AIDS. There’s no proof of their efficacy in any of these uses. The animals are captured, gutted, dried on sticks in kilns, and exported, mainly to China but also to Taiwan, Hong Kong, Vietnam, and elsewhere.

While it’s often argued that captive breeding relieves pressure on endangered species by providing an alternative source for trade, the report, Adding Up the Numbers: An Investigation into Commercial Breeding of Tokay Geckos in Indonesia, demonstrates that the opposite is true. Rather, it finds that wild-caught Tokay geckos are regularly laundered through Indonesia’s captive-breeding facilities on a massive scale.

Because Tokay geckos aren’t listed under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), their international trade isn’t subject to regulation.

In Indonesia, the harvest and export of wild-caught Tokay geckos are subject to quotas. Commercial breeding is allowed, and the government has given permission for six companies to export three million live captive-bred Tokay geckos a year, specifically for the pet trade.

Tokay geckos are found throughout Southeast Asia. Little is known about the impact of their trade, which is largely unregulated. Some countries, such as Indonesia, have export quotas for live, wild-caught Tokays. Photograph by Rouelle Umali, Xinhua Press/Corbis.

The report concludes that trade in those high quantities can be sustained only through the routine laundering of wild-caught individuals and their export as dead specimens.

From TRAFFIC’s Southeast Asia office, in Malaysia, Chris Shepherd, coauthor of the report, explains that it’s low-profile species like Tokay geckos that are often hardest hit by illegal, unsustainable trade.

What prompted the study?

It’s becoming increasingly obvious that so-called captive-breeding facilities are being used to launder large numbers of wild-caught animals into the global market. Indonesia exports exceptionally high numbers of animals declared as captive-bred, with Tokay geckos being among the most numerous. So numerous, in fact, that it’s very hard to believe—and therefore this study was carried out.

What are the economics of captive breeding?

In countries where enforcement levels are low, and capacity or policies to regulate captive-breeding facilities are weak, there’s a huge financial incentive and a very low risk for captive-breeding facilities to launder animals from the wild and export them as being captive bred.

Breeding animals requires huge investments and ongoing costs—housing the animals, caring for them, feeding them, etc. Where laundering is rife, a legitimate breeder wouldn’t be able to compete with those laundering wild-caught animals.

Tokay geckos can breed in captivity, but to imagine this being done in such quantities boggles the mind and is just ridiculous. The costs would be enormous, and the profits small. Taking them from the wild—paying villagers a few cents to collect them—and then exporting them immediately makes far more economic sense, despite it being against the rules.

How is the trade regulated?

Tokay geckos may be harvested from the wild in Indonesia under a quota system. However, if they are farmed, they don’t fall under that quota system. Any harvest of Tokay geckos from the wild outside the quota system is illegal. Note that the quota in Indonesia for wild-caught Tokay geckos stipulates that the animals are exported live, for pets, not kiln-dried.

Unfortunately, Tokay geckos aren’t listed in the appendices of CITES, and therefore international trade isn’t regulated. We strongly recommend the species be listed in Appendix II, which wouldn’t stop trade but would put in place a mechanism through which the trade could be monitored and regulated. To do so is in the interest of conservation and sustainable trade.

Under the current circumstances, it’s just a matter of time before the massive levels of trade wipe the species out from many parts of its range. It’s important to note that Tokay geckos are not just being exported from Indonesia but also from many parts of their range in South and Southeast Asia.

How big is the industry?

There are at least six companies claiming to breed Tokay geckos in large volumes in Indonesia alone. How many more such facilities there are in the region remains unknown. There are also many companies and wildlife traders operating outside of both the captive-breeding operations and the quota systems that are exporting huge volumes of Tokays from the wild, kiln-dried.

How is the captive breeding system regulated?

There are good regulations around the breeding of wildlife in Indonesia, yet these regulations are often ignored. Ideally, the farms would be monitored on a regular basis, and studies would be ongoing to ensure that the volumes of animals coming from these facilities are in fact realistic. And tools would be available for authorities in both exporting and importing countries to use to determine the likelihood of the specimens involved actually being captive-bred. Currently, it’s extremely difficult for authorities to determine whether the animals are wild-caught or captive-bred—and the dealers know this!

Can captive breeding work?

Captive breeding of wildlife for trade can be a sustainable industry, and can remove pressure from wild populations. Look at budgies—they’re traded around the world but are all from captive-breeding operations and not from the wilds of Australia.

This works due to a number of factors: Enforcement in Australia is a real deterrent—you’re likely to be caught and punished for smuggling wild birds. Budgies breed well in captivity, and they breed cheaply.

But this isn’t the case for all species. In many instances, regardless of the ability to breed animals, enforcement levels are not strong enough to be a deterrent. If the system is weak, unscrupulous dealers will, and do, take advantage of it to secure higher profits.

The authorities in Indonesia have the tools at hand, in the form of strong legislation protecting native species and regulating trade. But they should do more to ensure that a few unscrupulous traders aren’t taking advantage of the system and aren’t driving Indonesia’s wildlife towards extinction. These few traders are ruining the image of the country in many ways, and are undermining the Indonesian government’s conservation efforts, and any efforts to succeed in establishing legitimate and sustainable trade.

What needs to happen?

We strongly urge Indonesia, and other Tokay gecko range countries, to immediately list the Tokay gecko in Appendix III of CITES and to propose a stronger listing, in Appendix II.

While Tokay geckos are widespread in Asia, few if any species could stand this level of off-take. It’s only a matter of time before the Tokay gecko becomes yet another species on the long, and ever growing, list of species threatened with extinction.