Mongabay.com: The Changing Nature of Illegal Logging – and Illegal Logging Investigations – in Brazil’s Amazon

The changing nature of illegal logging – and illegal logging investigations – in Brazil’s Amazon

By Laurel Neme, special to mongabay.com

July 08, 2010

Continued from Top officials busted in Amazon logging raids, but political patronage may set them free

Operation Jurupari followed on several previous Brazilian Federal Police investigations into SEMA, including: Operation Curupira I (June 2005); Curupira II (August 2005); Mapinguari (2007), Arc of Fire (2008), Termes (April 2008); and Caipora (2008). It was led by Franco Perazzoni, Brazilian Federal Police “Delegado” (or chief), who, since 2006, has headed the environmental crimes unit in Mato Grosso and been responsible for about 300 investigations on environmental crimes, of which about 75% were on illegal deforestation in federal areas.

The Old System: Timber Documentation and Forgeries

The nature of the illegal deforestation has changed over the years. In 2005, at the time of Operation Curupira, the agency responsible for implementation, regulation and enforcement of Brazil’s environmental policy, IBAMA (the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources), controlled the transport and the trade of timber. They did it manually, as no integrated computer system for controlling the legal production and transport of timber existed. The local offices of IBAMA controlled forestry production and its commerce used handwritten logs and other documentation (like accountancy books). The main public document that authorized legal timber shipments was an ATPF (Authorization of Transport of Forest Products), which was issued to companies by IBAMA. The companies would then exhibit the ATPF to authorities during timber transport to show their logs were legal.

Each ATPF could be sold in the black market for about US$1,500 and could be used to “legalize” one or more transportations of timber extracted illegally from public areas. Although the ATPF contained some security items, there was intense fraud from 2000 to 2006, with many ATPFs either forged and stolen. Many authentic ATPFs were also sold by corrupt IBAMA officers and destined for sawmill owners and transporters.

Both Operations Curupira I and II focused on ATPF frauds and were joint investigations of Brazil’s Federal Police, Federal Prosecuting Office and the IBAMA comptroller. Under both of these operations, the investigations were based on monitoring telephones of some corrupt IBAMA officers, sawmill owners and transporters as well as on auditing the ATPFs of suspects.

The New System: Computerization and Planning

The New System: Computerization and Planning

Following the successes of Curupira I and II, the ATPF system was changed to a computerized tracking system, called SISFLORA, that works similar to a bank account. While IBAMA funds the system, it no longer provides the authorization for forestry plans, timber transport or other forest extraction. Instead, since 2006 the administration of the SISFLORA system in the Amazon states rests with the state environmental agencies or secretaries (e.g., SEMA in Mato Grosso).

While this new system is a vast improvement over ATPFs, it is not perfect. Whereas previously, the criminal activities focused on fraudulent or stolen ATPFs, especially by the sawmills and transporters, now the scam occurs directly within the Forestry Management Plans, with complicity of all those involved throughout the administrative and supply chain—from forestry and agronomy engineers to government authorities. The illicit schemes create “virtual” forestry credits on SISFLORA. Because these credits “legalize” illegal timber from other areas, this “credit” black market is extremely lucrative.

Fraud in the New System

Following its implementation, several Brazilian Federal Police and IBAMA investigations examined fraud within the SISFLORA system.

- Kayabi (2006) – investigated the illegal extraction of timber from Kayabi Indigenous territory.

- Mapinguari (2007) – investigated illegal extraction of timber from Xingu Indigenous territory

- Termes (2008) and Caipora (2009) – investigated highway patrol officers and some SEMA officers who were involved in illegal transport of timber (without authorizations)

- Arc of Fire (2008/2009/2010) – was an extensive operation against illegal deforestation throughout the Amazon (Para, Mato Grosso, Rondonia and Maranhao states). This was the first time GIS and remote sensing were used in both the investigations and their operational planning.

While Operation Jurupari had its beginnings within all of these operations, it had no official start or prompt. In 2008, Perazzoni received a lengthy 10,000 page report from IBAMA describing irregularities it had detected in the forestry management plans of Mato Grosso from 2006 and 2007. While the majority of cases were not on federal lands, those that were on federal lands were in already deforested areas.

Rather than focus on these already “lost” areas, which would have been, according to Perazzoni, like “picking up the pieces of a broken glass,” Perazzoni opted to focus on what remained intact and try to get a step ahead of the criminals and their “modus operandi.”

Operation Jurupari

Operation Jurupari

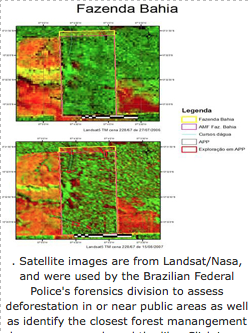

The Jurupari investigation sought out active forestry management plans that were being used to explore timber in federal areas and then identified corrupt officers in action. The operation started by using remote sensing to ascertain the more deforested areas inside federal parks and indigenous territories. It then pinpointed the nearest suspicious forestry plans and sawmills and cross-referenced data within SEMA systems to uncover possible fraud. When investigators uncovered a property or sawmill with suspicious comportment in the system (such as forestry inventories, forestry credits, etc.), they got the necessary judicial authorization for closer scrutiny (such as telephone and internet monitoring, auditing bank accounts, etc.). In this way, they were able to identify those people throughout administrative and supply chain that supported illegal logging.

Because the con occurred early in the administrative process at a technical level requiring specialized knowledge, detection of the illegal logging scheme was complicated. It was not simply a matter of detecting a counterfeit permit. Rather, it meant investigators needed to determine inventories were falsified, which in turn necessitated on-the-ground and technical verification of the volumes and species of wood present at specific locations. It also required proving that corrupt government officials, landowners, loggers and foresters knew of or supplied the fraudulent data and willingly applied for or approved the plans and permits based on what they knew was untrue information.

Because the con occurred early in the administrative process at a technical level requiring specialized knowledge, detection of the illegal logging scheme was complicated. It was not simply a matter of detecting a counterfeit permit. Rather, it meant investigators needed to determine inventories were falsified, which in turn necessitated on-the-ground and technical verification of the volumes and species of wood present at specific locations. It also required proving that corrupt government officials, landowners, loggers and foresters knew of or supplied the fraudulent data and willingly applied for or approved the plans and permits based on what they knew was untrue information.

Investigators used data from nearby properties and also official data of species that occurs in the region to establish the possibility of fraud. In some instances, such as where the dimensions of the property and its location indicated the plan overstated the amount of timber available (sometimes by 400%), or where the remote sensing images or official data demonstrated the area was already deforested, with no more commercial species in place, determination of fraud was relatively straightforward.

Normally, all logging requires an environmental permit (LAU) and a Forestry Management Plan (PMF), both of which are authorized by SEMA. The LAU (environmental permit) ensures the property is okay, meaning there is no illegal deforestation there or other legal problems concerning its location (such as it being inside a public area, etc.). It is accompanied by an inventory, which is produced by a forestry engineer and must show all the commercial species on that land, and a recent satellite image of area, which shows the property and its boundaries, access roads, topography, water and other physical features. The forestry engineer then signs a statement, called ART (Technical Responsibility Annotation), and assumes technical responsibility for the exploration on that area. Finally, these documents are verified by different sectors within SEMA (e.g., legal, GIS, etc.), who, on occasion, will visit the property. Given these steps, authorities could prove that an inventory or approval was purposefully falsified whenever it found fake inventories that were used to obtain credits which were then used to legalize timber that did not occur in a specific area.

Normally, all logging requires an environmental permit (LAU) and a Forestry Management Plan (PMF), both of which are authorized by SEMA. The LAU (environmental permit) ensures the property is okay, meaning there is no illegal deforestation there or other legal problems concerning its location (such as it being inside a public area, etc.). It is accompanied by an inventory, which is produced by a forestry engineer and must show all the commercial species on that land, and a recent satellite image of area, which shows the property and its boundaries, access roads, topography, water and other physical features. The forestry engineer then signs a statement, called ART (Technical Responsibility Annotation), and assumes technical responsibility for the exploration on that area. Finally, these documents are verified by different sectors within SEMA (e.g., legal, GIS, etc.), who, on occasion, will visit the property. Given these steps, authorities could prove that an inventory or approval was purposefully falsified whenever it found fake inventories that were used to obtain credits which were then used to legalize timber that did not occur in a specific area.

Operation Jurupari was notable both for its scale and the coordination among divisions. Using a combination of traditional investigative techniques such as on-the-ground surveillance and analysis, electronic monitoring of telephone and internet, financial audits, remote sensing and analysis of satellite images, and forestry management knowledge by the forensic scientists, Operation Jurupari was the first investigation in the environmental arena (and perhaps in the entire Brazilian Federal Police) where Brazil’s three law enforcement sectors of forensics, intelligence and field agents worked together in a completely integrated fashion—whereby each division supported and complemented the other by simultaneously and continuously providing information. It shows that, while the illegal timber traffickers have become increasingly sophisticated at hiding their crimes, the authorities or “timber investigators” are becoming increasingly adept at finding them.

Operation Jurupari was notable both for its scale and the coordination among divisions. Using a combination of traditional investigative techniques such as on-the-ground surveillance and analysis, electronic monitoring of telephone and internet, financial audits, remote sensing and analysis of satellite images, and forestry management knowledge by the forensic scientists, Operation Jurupari was the first investigation in the environmental arena (and perhaps in the entire Brazilian Federal Police) where Brazil’s three law enforcement sectors of forensics, intelligence and field agents worked together in a completely integrated fashion—whereby each division supported and complemented the other by simultaneously and continuously providing information. It shows that, while the illegal timber traffickers have become increasingly sophisticated at hiding their crimes, the authorities or “timber investigators” are becoming increasingly adept at finding them.