Mongabay.com: Operation Jaguar: Busting a Poaching Ring

From Mongabay.com

By Laurel A. Neme, special to mongabay.com

October 03, 2010

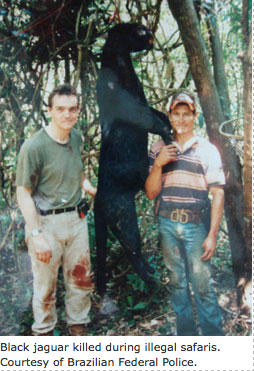

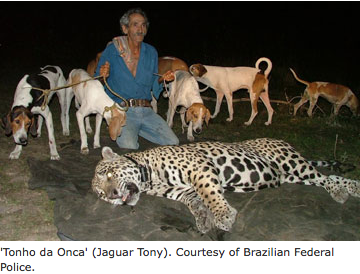

Twenty years ago Brazil’s most notorious jaguar hunter, Teodoro Antonio Melo Neto, also known as “Tonho da onça” or “Jaguar Tony,” swore off poaching after logging 600 kills. The foe turned ally of the jaguar then convinced environmental and research institutes, such as the non-governmental organization Instituto Pró-Carnívoros, of his about face and to employ his tracking skills for conservation. Thus began years of assisting these agencies find the animals so that they could monitor their movements and research their habits. His dramatic change of heart even became the subject of a children’s book titled Tonho da onça, which related a conservation message. But on July 20, 2010, “Jaguar Tony,” now 71 years old, revealed his true spots when federal agents arrested him along with seven others preparing for another in a long series of illegal hunts.

The Brazilian Federal Police and Brazil’s Environment Agency (the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Natural Resources or IBAMA) first became suspicious of Jaguar Tony’s duplicity following reports of missing radio-collared jaguars that had been part of a research project. Evidence of jaguar carcasses on farms in the Pantanal reinforced their qualms and, in October 2009, they launched a joint investigation, code-named Operation Jaguar, that culminated in the 9:00 am raid on a farm in Nova Santa Helena, a small town over 600 km north of Cuiabá in the Sinop region of Mato Grosso state. Led by the Brazilian Federal Police, 60 officers executed arrest and search warrants across seven municipalities in three Brazilian states (Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso du Sul and Paraná). They timed their bust to stop yet one more kill.

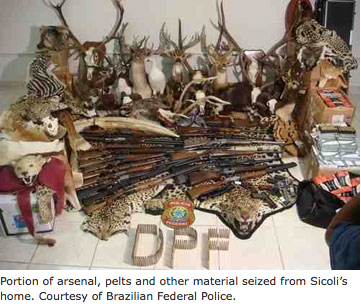

When agents arrived on the Pantanal farm, Jaguar Tony, his son Moraes Marco Antonio de Melo, and the organizer of the safaris, dentist and university professor (at Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná) Elisha Augustus Sicoli, along with five foreign clients (four Argentines and one Paraguayan), were gearing up to depart on another illegal trek. Jaguar Tony fled (and is believed to be hiding on a farm in the Pantanal) but police arrested the others. They also seized a vast array of weapons and ammunition from Sicoli that, according to the Chief of the Brazilian Federal Police in Cascavel, Paraná, was larger than the police’s own arsenal. During searches of the homes of Sicoli and two other alleged gang members, Célio Neri Prediger (in Corbel) and Humberto Fiori Filho (in Miranda), police also found hundreds of photographs documenting jaguar, elephant and rhino kills that now will provide important evidence against the defendants.

Jaguars are protected in multiple venues. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) includes them in Appendix I, which prohibits their commercial trade. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists jaguars as endangered, and they are classified as near threatened on IUCN’s 2008 Red List. Under Brazilian law, jaguars are considered an endangered species.

Nobody knows how many remain, as their elusive nature and remote and forested habitat make population surveys extremely difficult. Estimates of wild jaguar populations worldwide range from between 8,000 to 50,000, with poaching and habitat loss the most significant threats. According to the IUCN Red List, about half of the animal’s distribution is in Brazil, where the Amazon and Pantanal provide critical habitat. The Pantanal, one of the main areas targeted by this illegal safari hunting gang, is the world's largest wetland with over 54,000 square miles (close to 140,000 km²) of rivers, seasonally flooded grasslands and forests, an area about the size of the state of Illinois or the country of Bangladesh. While population studies are ongoing, scientists (Marianne Soisalo from University of Cambridge and Sandra Cavalcanti from Utah State University and Instituto Pró-Carnivoros reporting in the May 2006 Biological Conservation) estimate jaguar densities in the Brazilian Pantanal at 6.6-6.7 adults per 100 km² (implying perhaps 10,000 in the area), and the British journalist Nigel Richardson reports in The Telegraph that the Pantanal is home to between 4,000 and 7,000 jaguars.

Because 95 percent of land in the Pantanal is privately owned, with 2,500 ranches and up to 8 million cattle, the area is replete with jaguar-livestock conflict. Jaguars often feast on cattle. Consequently, local farmers detest jaguars, and kill or hire others to kill the felines on sight.

Under Brazil’s environmental crimes law (Lei de Crimes Ambientais - 9.605/98), killing jaguars is a crime. While, in theory, article 37 of that law establishes an exception to protect herds from problem predators, IBAMA must first authorize that exception. However, an IBAMA authorization of killing jaguars is an extremely unlikely action as there are many other legal ways for an owner to be compensated. Rather, the capture of the animal and its release in other areas is a far more likely course of action than giving permission for it to be killed.

The illicit jaguar poaching gang took advantage of the tension. By arranging these illegal safaris, they not only earned money from tourists eager to hunt big game but also provided a service to farmers, who rid themselves of a deadly threat to their herds. Although they did not pay for the privilege, ranchers did allow the hunts on their land and also often supplied the hunting dogs used to locate the large cats.

The scheme itself was straightforward. Sicoli, in collaboration with several others, served as the front man to organize illicit sport hunting safaris in Brazil (for spotted and black jaguars and pumas in the Pantanal in Mato Grosso do Sul and Mato Grosso or Iguaçu National Park in Paraná) and Africa (for elephant ivory). He also supplied equipment, namely the weapons appropriate for the desired prey—lower caliber to avoid damage to the Brazilian cat pelts and higher caliber to stop the elephants, rhinos and hippos targeted in Africa. The gang had several “branches”—in the cities of Cascavel, Corbel and Curitiba in Paraná; in Corumbá, Miranda and Bodoquena in Mato Grosso do Sul; and Rondonópolis and Sinop in Mato Grosso—and flew clients into the Pantanal farms or other locales via private planes.

In Brazil, Jaguar Tony and his son served as guides. The skilled father-son team used specially trained hunting dogs to track and encircle the jaguars or force them to the top of trees, where they became easy targets. Hunters then photographed their conquests and had the choice of either destroying the carcasses or making them into trophies. Another member of the gang, Fernando Chiavenato, provided these taxidermy services. (Chiavenato initially fled arrest in Curitiba but turned himself in a few days later.)

The price was reasonable. The $1,500 per person package included a five to seven day Brazilian safari as well as air and ground transportation, meals and lodging. (A similar African safari cost $3,500 per person.) The lead investigator for the Brazilian Federal Police, Paulo Nomoto, notes that this poaching ring likely ran these illegal safaris as more of a “hobby” than a profit-making venture, and says authorities do not know how much the poaching ring earned over the years.

Members of the organized poaching gang face criminal charges under Brazil's Environmental Crimes Law (articles 29 and 32) and, if convicted, could receive penalties of six months to one-year imprisonment. They also face criminal charges for illegal possession and use of a firearm (articles 14, 15, 16 and 18 of Law No. 10,826 of December 22, 2003), with a penalty of up to four years in prison, and for conspiracy (Section 288 of the Criminal Code).

In addition, the eight men caught “red-handed” in the act of an illegal hunt also must pay administrative fines for killing endangered species. Each of the five foreign hunters must pay fines of R$5,000 (US$2,850) while Sicoli, Jaguar Tony and his son were assessed fines of R$10,000 (US$5,700). However, these monetary penalties are separate from the criminal charges and the gang members remain in detention.

The impact of this single gang on jaguar populations is potentially significant. According to Alessandre Reis, Divisão de Comunicação Social of the Brazilian Federal Police, the scheme operated for 20 years, with up to 50 jaguars killed each year, or 1,000 animals overall. Consequently, jaguars killed by this single ring may represent as much as one-quarter of the area’s wild jaguar population and up to 12 percent of the world’s. Whatever the number, Operation Jaguar and stopping this gang will go a long way toward helping the species.