Mongabay.com: Mexico has big role in the illegal parrot trade

By Laurel Neme, special to mongabay.com

May 30, 2010

Juan Carlos Cantu, Director of Defenders of Wildlife’s Mexico office, spoke with Laurel Neme on her "The WildLife" radio show and podcast about the illegal parrot trade in Mexico and how his innovative research into the trade was used by the Mexican Congress to reform that country’s Wildlife Law to ban all trade in parrots.

This interview originally aired March 8, 2010.

The illegal pet trade is probably the second-biggest threat facing parrots in the wild, with only habitat loss rating higher, and the impact is disturbing.

"Several species have seen their populations crash to the point of being critically endangered due to the enormous illegal extraction from the wild," says Juan Carlos Cantu, Director of Defenders of Wildlife's Mexico office. "If the trade is not stopped, several species will disappear from the wild in the next 10 to 20 years."

Defenders of Wildlife documented this threat in a 2007 landmark study which found between 65,000 and 78,500 parrots are illegally trapped in the wild in Mexico every year.

While thousands of these parrots are smuggled across the border into the United States, the study uncovered that about 90 percent of illegally trapped Mexican parrots are actually destined for Mexico’s domestic market. This is a big shift from the 1980s, when smugglers illegally brought 150,000 Mexican parrots into the United States each year. With stronger laws and enforcement, that number has declined to about 9,400 parrots. At the same time, Mexico’s domestic market has expanded, with the majority of illegally caught Mexican parrots supplying domestic demand. The past 10 years has also seen an explosion in smuggling of exotic parrot species into Mexico. Currently, over 100,000 illegally enter Mexico from South and Central America annually.

The illegal trade kills thousands of birds, often during transport when they are packed in tubes or cages with inadequate ventilation, food and water. Cantu estimates 75 percent of Mexico’s illegally captured birds, or about 50,000 to 60,000 parrots, die each year before reaching their final destination.

Juan Carlos Cantu directs and implements all programs of the Mexico office of Defenders of Wildlife. Before joining Defenders, Cantu coordinated the oceans and forestry campaigns for Greenpeace Mexico where he conceived and led the campaign to create the world’s largest national whale sanctuary in all Mexican waters. He also co-founded a Mexican non-governmental organization, called Teyeliz, where he wrote many reports on the illegal wildlife trade. He’s also worked for the Sea Turtle Restoration Project to get Mexico to use sea turtle excluder devices, and held several other positions.

Juan Carlos Cantu joined Defenders of Wildlife in 2002 and in 2007 published The Illegal Parrot Trade in Mexico: A Comprehensive Assessment that was instrumental in the Mexican Congress’ decision to reform the country’s Wildlife Law to ban all trade of parrots.

Over the years, his efforts have helped get many endangered species of parrots, including the yellow-crested cockatoo and the blue-headed macaw, uplisted to Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). He has also created 5 comic books on the illegal trade of sea turtles and started a radio show called “Supervivencia”, which creates public awareness about wildlife issues and is the highest rated show on the station with over 400,000 listeners.

An Interview with Juan Carlos Cantu

Laurel Neme: What first got you interested in the illegal parrot trade?

Juan Carlos Cantu:The Mexican people and the Mexican culture has been involved with parrots since pre-Colombian times. The Aztecs, and all the people that lived in Mexico and also in Central and South America, were very much involved with parrots.

Laurel Neme: How so?

Juan Carlos Cantu:They used to capture them for pets and they also ate them. But most importantly, they were very interested in parrots because of their feathers.

Laurel Neme: Would they use the feathers?

Juan Carlos Cantu:Yes. They used to make clothes with the feathers and also for various forms of art. They were so important at that time that the Aztecs – they were a very warrior-like people – every time they had a combat with another group of indigenous people and conquered them, they would ask as tribute packs of parrot feathers. From some people in southern Mexico, at one point, they would be asking for 20,000 packets of parrot feathers.

Laurel Neme: So it was almost like money, or gold?

Juan Carlos Cantu:Exactly. They were very, very, very important.

And after that, when the Spanish came, and conquered America, most of trade with parrots basically disappeared, but still they kept capturing parrots for pets. And so in Mexico we have had parrots for pets for hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of years, many, many, many centuries. So it was part of Mexican culture to have a parrot. At one point it was said that every family should have a parrot.

Laurel Neme: Was it just as pets or other uses too, like food?

Juan Carlos Cantu:Mostly as pets. And at one point they would still be eating parrot in southern Mexico but then the government forbid it. The thing with parrots is that they do eat several seeds and fruits that are very toxic. So people would get sick from eating parrots. So it was banned.

Basically people were just using parrots as pets. But there was a huge overexploitation of the population of parrots. And afterwards, around the 70s and 80s, parrots became very popular in the US and Europe. And so most of the parrots were captured to be exported into the US, or even smuggled into the US. Hundreds of thousands of parrots were going into the US and to Europe.

Laurel Neme: Were they all types of species of parrots? Or were there particular species that were targeted?

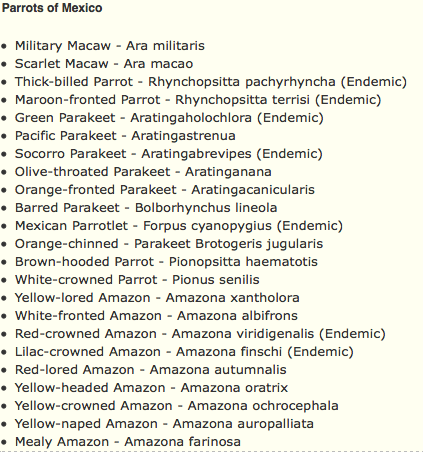

Juan Carlos Cantu:In Mexico we have 22 species of parrots and macaws. 20 or so species would be targeted. But mostly it was Amazon parrots. There are many, many species of Amazon parrots, and also macaws.

Laurel Neme: Did the trade have an impact on the populations of these species?

Juan Carlos Cantu:By the end of the 80s a lot of these species were now endangered. Their populations have declined so much in Mexico they started to ban the capture of these species. Up until 2 years ago, capturing parrots was still legal – but only for very few species, around 5 or 6 species. Even though capturing parrots in Mexico was legal, most of the parrots there were being captured illegally by poachers.

Laurel Neme: So to capture a parrot legally, what would that take?

Juan Carlos Cantu:Well, the environment ministry would have to issue a permit to capture parrots and to sell the parrots. But the thing is, there was really no control. They tried for decades to control the capture and trading in parrots. Nothing really worked. Because every time they issue a permit, for example they would issue a permit for a specific species, for the number of species that could be captured. There was really no control after they issued the permit. Trappers would just go out into the field and they would trap any species they wanted. They would trap as many as wanted. There was nobody there to monitor what they were doing. So in fact they were capturing five or up to ten times as many parrots as the permit allowed. So what was happening was that the legal trade in parrots was used as cover for the illegal trade.

Laurel Neme: Was there any monitoring going on?

Juan Carlos Cantu:For Mexican authorities to monitor that legal trade was very difficult because there was really no way to know which parrot had been captured legally and which one was captured illegally. One of the things they tried to do is that they would put bands on the parrots’ legs so that they would know which parrot was captured legally.

Laurel Neme: Did that work?

Juan Carlos Cantu:The trappers would capture a parrot, they would not put the band on the leg, and when they were selling the parrot to a customer, they would say okay, if you want the parrot without the band, it costs that much. But if you want the band leg, it will cost you a lot more. In that way, they could use the bands many, many, many times.

Laurel Neme: Could the band come on and off?

Juan Carlos Cantu:That was one of the problems. Really, the only way for a band to work is if you use a closed band that can only be put on a parrot leg when they are very young, when they’re a chick. Those types of bands you cannot put them on when they’re adults. But the bands they were using were the type you can open up. So in fact, there was no control at all. Everybody knew, even the authorities, that there was a huge illegal trade in parrots. What they say was that well, we know illegal trade is going on but we don’t know the volume, we don’t know who’s doing it, we don’t know which species are being affected, we don’t know in which regions. We just don’t know anything because it is illegal. And since it is illegal we cannot study it or control it.

Laurel Neme: So what did you do?

Juan Carlos Cantu:So what we did, a few years ago, we made the research ourselves. Defenders and other NGOs, like Teyeliz, we did the research. It took us two years. What we did was we interviewed the trappers.

Laurel Neme: How did you do that?

Juan Carlos Cantu:The thing is that, in Mexico, the trappers work in unions. First we talked with the leaders of the unions. And then through the leaders we were able to talk to the trappers. Now, these unions, they work legally. But we know for a fact, that they trap illegally most of the time.

Laurel Neme: Were they willing to talk with you?

Juan Carlos Cantu:Yeah, incredibly. Incredibly. They didn’t mind talking about what they did because, in their minds, they were really not doing anything wrong. They were just trapping birds. Most of them have been doing that for all their lives. They learned the trade from their fathers and grandfathers. So it was just a normal thing to do. They really didn’t believe that what they did was really illegal. Even though the laws have changed they just think of the work as something that was done wrong, and they were just doing what they had been doing all their lives. So they were very open about how they trapped parrots, how many parrots they trapped. We weren’t able to talk to all the trappers but we talked to a lot of them, enough to extrapolate to the rest of the trappers.

Laurel Neme: What did you find out?

Juan Carlos Cantu:We found out they were trapping more than 75,000 parrots a year illegally. The legal permits for trapping would only account for only 2,000 or 3,000 a year. So the immense majority of parrots being trapped in Mexico were being trapped illegally.

Laurel Neme: And then what did you do with these findings.

Juan Carlos Cantu:When we finished the report, we took it to the authorities and showed them what was going on and told them you have to stop the trade in parrots because the measures you are taking to control the trade are not working and you’re only covering up the illegal trade. And populations are really declining. We now have, of the 22 species, 11 species are endangered, [with a total of] 20 species in some category of risk. Some are threatened and some are protected. The thing is, the legal trade in parrots is driving the parrot populations to extinction because they’re covering up the illegal trade.

Eventually we took the information into Congress and we were able to convince the Deputy Chamber and the Senate to change the law, so that all parrot trapping in Mexico was banned back in October of 2008. So now it is totally forbidden to capture parrots or to trade with wild parrots in Mexico.

Laurel Neme: What about possess them or sell them?

Juan Carlos Cantu:You cannot do it with wild parrots. The thing is, since a lot of people already have wild parrots as pets, they can keep them, but they cannot sell them or trade them. And now you cannot buy wild parrots. You can still buy captive bred parrots, especially from exotic species. Mexico has become one of the biggest importers of exotic species of parrots in Latin America. And this has been happening for the past 10 or 15 years. It has been growing. Now, most of the parrots you see in pet shops or in markets or by street vendors are species of parrots from Africa or Asia or from South America.

Laurel Neme: What’s happened since the ban was passed?

Juan Carlos Cantu:Since then we have been monitoring street salesmen and markets and pet shops and we have talked to trappers also. And there has been a change. With the trappers, we talked to them and they have told us that most of them have stopped trapping parrots altogether. Some of them have taken to starting their own captive breeding programs, especially with exotic parrot species. And we have seen that most of the street birdmen and markets, most of the parrots being sold are exotic species now, and also in pet shops. We started a huge national campaign to alert the people that the law had changed and it was now illegal to buy wild parrots.

Laurel Neme: What did you do for this public awareness campaign?

Juan Carlos Cantu:We have been working with several institutions. Now we are working also with the Environment Ministry, we have now changed their minds and now they are working with us. We created a web page to give information on all 22 species of parrots and macaws, on the law, and on what people can do to help the conservation of these species. Basically, the message is not to buy wild parrots. And so we produced a bunch of posters with the message and we have been distributing posters all over Mexico. We created a whole bunch of materials, like children’s books, coloring books, story books, comic books for young people and adults, a teacher’s kit, stickers, and we have been distributing all of these materials with NGOs and with scientists and with people who want to work with this campaign and want to help distribute new material and distribute the information. It has been very successful. There’s a huge amount of NGOs working in the campaign and there’s also several institutions working with us. A lot of scientists are working and helping us distribute the information and the posters, putting it up everywhere. And now there’re a lot of people creating conservation programs for parrots using the material that we have created.

Laurel Neme: Why have you focused on this public awareness approach?

Juan Carlos Cantu:The thing is, it’s very difficult to chase around poachers and traffickers and try to control them. So the idea behind the campaign is to try to get people to stop buying wild parrots. So if we can decrease demand, the offer [illegal supply] is going to decrease as well. In that way we’re going to be able to get the ban to really work.