Mongabay.com: Leuser’s Legacy: how rescued orangutans help assure species survival

Meet two blind orangutans: Leuser and Gober, their offspring, and the people of the SOCP rescue group. Together they’re creating a future for Indonesian orangutans.

- Agribusiness is rapidly razing the prime forest habitat of Sumatra’s 14,600 remaining orangutans; replacing it with vast stretches of oil palm plantation. The species’ population is predicted to plummet unless a way is found to protect their habitat.

- SOCP, the Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Program, is working to rescue orangutans left without their forest homes by new oil palm plantations; relocating the animals to intact forests not included in proposed concessions.

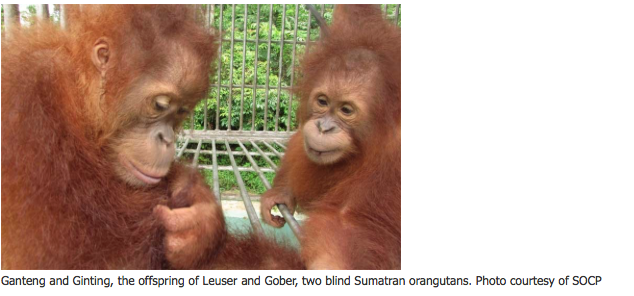

- This story moves beyond the statistics of wildlife conservation and follows the lives of a single family of orangutans: blind parents Leuser and Gober, and their offspring Ganteng and Ginting — animals left homeless then rescued.

he adolescent orangutan was captured in the forests of Sumatra by a soldier at the height of the Aceh province civil war for independence. By February of 2004, this orangutan was on his way to becoming the illegal pet of a police lieutenant in Jakarta. That’s when a team from the Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Program (SOCP) and the Ministry of Forestry’s Conservation Department in Aceh (BKSDA Aceh) intervened and confiscated the five-year-old male ape.

They called him Leuser, in honor of where he came from — the Leuser Ecosystem.

Indonesia’s Leuser Ecosystem, on the northern end of the island of Sumatra, is a 10,000 square mile (2.6 million hectare) biodiversity hotspot that encompasses a variety of terrain from mountains and tropical rainforest to lowland forest and peat swamps. It’s shaped like a pair of lungs and straddles two provinces: with North Sumatra holding 15 percent of the region, and Aceh including the other 85 percent.

Leuser is often referred to as “the last place on earth” because it is the only remaining habitat shared by critically endangered Sumatran elephants, rhinoceros, tigers and orangutans.

The Indonesian government designated the Leuser Ecosystem as a National Strategic Area in 2008, not only because it’s a vital habitat but also because it provides important environmental services — carbon storage in its peat swamps and forests, and protection from floods and drought as a critical watershed.

Even so, palm oil barons, illegal loggers and mining companies want to develop it. And in 2013, the provincial government issued its controversial Aceh Spatial Land Use Plan, which doesn’t mention the Leuser Ecosystem at all (despite a federal requirement to account for national strategic areas). The land use plan allowed for the opening of huge swaths to forest clearing and road construction within the Leuser ecosystem.

That further threatens Sumatran orangutans, whose populations are declining rapidly due to habitat loss. While a new study using nest decay surveys doubled the estimated population to roughly 14,600 in 2015, that research also warned that numbers will continue to plummet, likely by 14 to 33 percent over the next 15 years.

Victims of agribusiness development

Clearing the land for oil palm plantations hurts orangutans, who not only lose their homes and food but come into increasing contact — and conflict — with farmers and villagers.

When a palm oil company goes in, it fells the timber and then sets fire to whatever remains to make way for oil palm seedlings — planted in long marching rows. This slash and burn technique is seen as a quick way to clear land for new plantations —yet it creates many interconnected problems.

A lot of the cleared land is peat forest that burns like a roaring barbecue. And even when fires above ground die, fires underground can continue for months and spread to new, unintended, places. The fires not only destroy massive amounts of former forest, but also release huge amounts of greenhouse gases. In late 2015 alone, Indonesia’s record fires — triggered by a combination of bad land use management and one of the strongest El Nino’s in history — burned through tens of thousands of hectares, which resulted in haze, respiratory infections in up to 500,000 people and emissions of 1.4 billion tons of CO2-equivalent greenhouse gases, more than Japan’s annual release.

While it’s illegal to capture, kill, or keep an orangutan as a pet in Indonesia, prosecution is rare and orangutans often meet these fates.

Leuser, the adolescent organgutan, was one of the “lucky” ones confiscated by authorities and brought to a rescue facility.

Orangutan rehabilitation

Leuser was first brought to SOCP’s quarantine center near Medan, where all new arrivals spend 30 days in quarantine for medical exams, treatment and to ensure they carry no illnesses that could infect others. They are then typically transferred to one of two locations, Jambi or Jantho, for release back to the wild.

By design, both locations are outside the Leuser Ecosystem — something done as a sort of species insurance policy. The Leuser Ecosystem is home to roughly 85 percent of the world’s remaining wild Sumatran orangutans. Yet that concentration is of concern to scientists, because a single disease outbreak could wipe out the entire population.

To safeguard the species, SOCP is establishing two additional and separate orangutan populations — one at Jambi in southeastern Sumatra, on the edge of Bukit Tiga Puluh National Park, and another at Jantho, in northern Sumatra in and around the Jantho Pine Forest Nature Reserve.

Jambi was chosen because of its large contiguous block of protected lowland forest. The effort began in January 2003, and so far SOCP has released around 185 orangutans there.

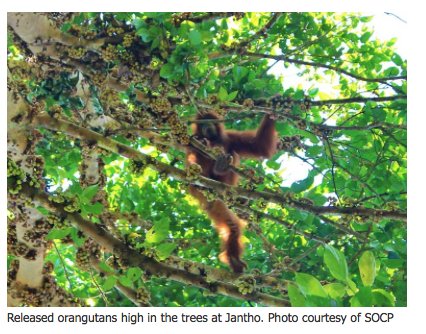

Jantho was established as a second release site in 2010, after the Aceh government decided that all illegal pet orangutans confiscated in Aceh should be released within that province. The Janthro area was selected because it provided prime orangutan habitat of rich lowland forest with a plethora of fig and other fruit trees, the staple food for these great apes. Releases began in March 2011, and to date more than 80 have been successfully relocated.

Land conversion for agribusiness has led to a large number of orangutan rescues throughout Indonesia, as noted by the lengthy State of the Apes 2015 report issued by the Arcus Foundation, and rehabilitation centers across the country are at full capacity. In Borneo, for example, as of December 2014, there were 489 orangutans living at the Nyaru Menteng Orangutan Reintroduction Center in Central Kalimantan, a number well above its intended capacity.

This is a common situation throughout Borneo. Orangutans can spend years living in a rescue facility because there are few release sites. That’s due, in part, to a federal directive (Ministerial decree 280 1995) which requires that releases not take place where there is already an existing wild population. Borneo’s orangutans seem able to tolerate more forest disturbance than in Sumatra, and so wherever there is a decent bit of forest, there’s almost always some orangutans using it. That makes it hard to find forests in Borneo that contain zero members of the species. Finding suitable release locations is further hampered by the fact that much forest is already under concession and waiting to be exploited, or too high in altitude and not good habitat. As a result, rescue centers in Borneo receive a lot of homeless orangutans but struggle to get them out to the forests again.

In Sumatra, there are good forests without orangutans, so SOCP takes a different approach, releasing its rescued orangutans at Jambi and Jantho. This has the additional benefit of building two populations of Sumatran orangutans separate from the Leuser Ecosystem.

SOCP hopes to release around 25 to 30 orangutans each year until there are at least 350 at each location. That’s the number, SOCP director Ian Singleton says, that can ensure a viable and sustainable community of more than 250 surviving, thriving and even more importantly, breeding orangutans.

After his quarantine, Leuser was transferred to Jambi in June 2004 to begin reintroduction training — learning how to find food, and how to build a nest. Staff showed him materials in the forest so that he could practice bending, breaking, and shaping tree branches into an orangutan’s characteristic sleeping nest. Through trial and error, watching other orangutans and the staff, Leuser learned forest pathways and experimented with feeding behaviors. By December, he was back in the wild.

SOCP staff monitor released orangutans, and over the next couple years, they spotted Leuser from time to time. They say that he took to the forest like he’d never left.

But that didn’t last long.

In November 2006, SOCP received a call saying that villagers had captured an orangutan on a plantation, 40 kilometers (about 25 miles) from the park boundary. A team moved in and quickly recognized the orangutan. It was Leuser.

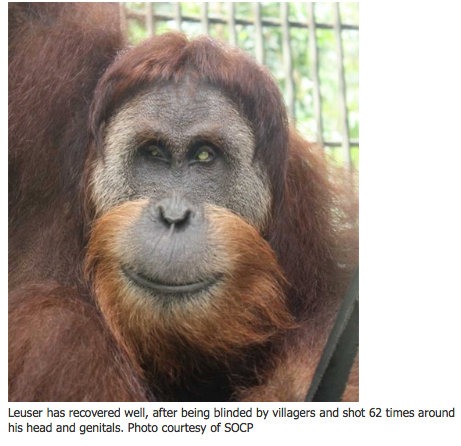

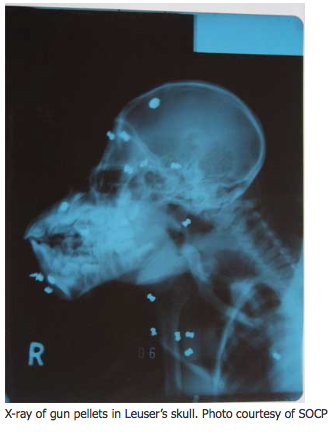

He was in bad shape. He had a 40 centimeter (nearly 16 inch) cut down his right leg and his body was riddled with air rifle pellets — 62 of them concentrated around his head and genitals. Both his eyes had been shot.

The team took Leuser back to the quarantine center. Veterinarians could only safely remove 14 of the 62 pellets. He was left totally blind.

Prosecution of crimes against orangutans

Three villagers were prosecuted for shooting Leuser and received 6-month jail terms. They claimed they wanted to capture the animal and sell it to an orangutan project, yet evidence suggested they shot Leuser just for fun.

While orangutans are protected by Indonesian Law No. 5/1990, prosecutions are unusual. A 2009 report, The Indonesian Chainsaw Massacre by Nature Alert and the Centre for Orangutan Protection, estimated that 2,500-3,000 orangutans are killed or maimed every year with virtually no prosecutions.

Leuser’s case was different. It marked “the first time somebody had gone to prison for shooting orangutans,” said Singleton. “If you add up the 3,000 plus confiscations in Indonesia since the 1970’s, only a handful have been prosecuted, and such cases are most always for selling or trading one.”

The first prosecution of an illegal orangutan owner in Sumatra came in February 2012, when an illegal wildlife trader in Medan, North Sumatra was sentenced to seven-months in jail for owning and selling orangutans.

In April of that same year, employees and managers of an oil palm plantation in East Kalimantan in Borneo were convicted of killing orangutans and other species after their company offered a bounty for the dead animals. The men received about $110 for each dead orangutan. Financial records indicated they had killed at least twenty. They received fines and eight-month prison terms. While noting the sentence was too little too late, the Centre for Orangutan Protection also recognized a shift toward tougher penalties, saying that “previously, it was almost impossible to imprison them.”

Such bounties and “pest” control are not unique. According to State of the Apes 2015, an estimated 750–1,800 orangutans were killed in 2007 just in Kalimantan, the Indonesian portion of Borneo, as a result of deforestation and agricultural development.

In December 2014, the Bornean Orangutan Survival Foundation in Nyaru Menteng took in a female orangutan wounded by 40 shotgun pellets and with broken arms and legs — inflicted at the Barunan Miri palm oil estate, a subsidiary of the Makin Group.

While she later died from her injuries, Leuser’s story has a happier ending. He’s made a full recovery — except for his blindness — and lives at the SOCP’s center. While he can’t ever return to the wild, his story has developed a new fascinating chapter through his relationship with another blind orangutan, Gober.

Gober’s Story

Conflicts often occur when orangutans, with nowhere else to go and little else to eat, raid crops. Such was the case for Gober, a mature female orangutan living in an isolated patch of mixed agro-forest near the villages of Citra Kasih and Sampan Getek in the Langkat District of North Sumatra. Already elderly and blind from cataracts, she had started relying on crops to survive — a recipe for disaster.

Fearing for her safety, SOCP captured Gober in November 2008 and brought her to the quarantine center. She hated captivity and feared people, probably because of the years she had likely spent being yelled at or shot at, or harassed with sticks and stones, by farmers. Already underweight, she didn’t do well at first. To improve her quality of life, the SOCP team made an unusual decision, introducing her to Leuser.

SOCP normally separates mature males and females to prevent pregnancies. Given the hundreds of orangutans already in captivity with no place to go, the researchers don’t want to add to their numbers, while also preferring that mating happens naturally back in the forest.

But Gober’s case was different. Depressed from captivity and with no prospect of release due to her blindness, she needed a mental boost. A baby could provide that and then eventually be released.

Shortly after meeting Leuser in June 2010, Gober became pregnant. On January 21, 2011, she gave birth to twins, a male named Ganteng and a female named Ginting — a very rare occurrence, and the only orangutan twins ever born to parents who were both blind. Gober proved to be a capable and devoted mother and reared the twins with no problems, though she still apparently hated captivity and humans. As she reared her young, she became even more stressed by people near her cage.

Finally, in an attempt to improve the tense situation, an Indonesian ophthalmologist offered to perform the country’s first cataract surgery on an orangutan. (One had been performed in Malaysia in 2007.) The operation took place on August 27, 2012 and was a success. Gober regained her vision — and a ticket to freedom.

Back to the forest

With her eyesight back, Gober was ready to be returned to the forest. But there was a complication: in the wild, young orangutans normally stay with their mothers until age 10 or 11. To ensure the best chances of success and survival, the SOCP team decided to wait until the twins were four years old before releasing the family. The researchers conjectured that, younger than four and the babies would hang onto their mom while she moved from tree to tree — a lot to ask because there were two of them. At age four, the young orangutans would be old enough to climb and feed themselves, but still young enough to stick close to their mother for protection and to learn survival skills.

Gober and the twins were moved to Jantho on December 5, 2014. After a month at the reintroduction station, during which time they became acclimated to the forest and the foods they’d encounter there, the family was finally released.

But things didn’t go as planned.

While Gober and her daughter, Ginting, took to the forest quickly, Ganteng wouldn’t follow. The young male clung to the trunk of a small tree as his mother and sister moved farther away. She came back, but he still wouldn’t join them.

“I was surprised,” Singleton said. “It was difficult when Ganteng didn’t follow her. She may have thought her survival in the forest and that of her daughter outweighed the risk of Ganteng being left behind.”

“We all resigned ourselves to the fact that this was how it was going to be from then on; Gober and Ginting living free, Ginting learning everything she needed to know from her mum. And Ganteng having to play catch up later, when ready to try on his own, without his mum’s care and support.”

Initially, Gober and Ginting did well in the forest.

Ginting “was showing signs of increasing confidence as a wild orangutan,” Singleton wrote on his blog. “Not only was she now finding her own fruits to eat in the trees, she had also learned to process and eat rotan [rattan] stems, just like her mother. This is an extremely useful skill as rotan is almost always available as a fall back food, when other foods are scarce. It’s also notoriously thorny and spiny, requiring extremely careful processing to do it safely.”

Singleton spotted the two animals several times over the weeks following their release, and each time “got a huge sense of satisfaction seeing them both high in the trees, acting like they were totally at home in the forest and ecstatically happy to be there.”

“Ginting’s future seemed all but assured,” he wrote. “She would grow up as a wild orangutan and eventually become a founder of the new orangutan population being established in Jantho. Gober would spend the rest of her days free once again, as she had spent most of her life, only this time in a far better quality, richer forest than she had ever known before. Ganteng would still get his chance eventually too, and with a little luck also meet up with his mum and sister again as a wild orangutan.”

So, it was a huge shock when, in May 2015, the monitoring team discovered Ginting’s body dead at the base of tree.

SOCP can only hypothesize about what happened. The inexperienced Ginting could have fallen from a tree by accident; or, equally plausible, she could have fallen after being slapped or pushed aside by a male orangutan interested in her mother — Gober is currently one of very few sexually mature females living in Jantho.

“The average age of release is between 5 and 7, so the majority of orangutans there are now 10 to 12 years old,” Singleton explains. “Wild females tend to give birth to their first infant when they’re around 15 years old. That means most of the females released in Jantho won’t be sexually receptive for a few more years yet. That makes even elderly females like Gober a major focus of interest for the larger males in the forest.”

Males can be aggressive if a female resists, and mating might involve violent slapping, grabbing or biting. A young orangutan like Ginting could easily have been knocked to the ground and killed in such a struggle. — a reminder that orangutans face other dangers in the wild besides those placed in their way by human beings and their oil palm plantations.

Hope — at Jantho, Jambi, and in the Leuser Ecosystem

Life goes on. The blinded Leuser remains in captivity, and will do so for the rest of his life. SOCP is currently developing the Orangutan Haven and Wildlife Conservation Education Centre, a 46-hectare (113 acre) natural area for orangutans like Leuser, who can’t survive in the wild. It will be the first such facility of its kind.

While he will never go back into the forest, his legacy lives on through his son Ganteng and mate Gober.

Gober is now a fully wild orangutan. With her eyesight restored and her release into quality primary forest habitat, her quality of life is much improved. She may even be pregnant again.

Ganteng turned five in January 2016. He has progressed quickly thanks to intensive SOCP training. He is now staying longer in the forest and showing many new skills, from finding fruit to building nests — he is, at last, behaving like a wild orangutan.

In another 5-6 years, many of the released animals at Jantho and Jambi will reach sexual maturity, and hopefully a new wild generation of orangutans will be born in Indonesia’s forest — far from their former home in the Leuser Ecosystem, but offering “insurance” for the future of the species and a hedge against the harm done when humans convert forests to croplands.

It’s not easy to establish new orangutan communities, but because of SOCP and other organizations like it, prospects are growing a little brighter for our red-haired primate cousins.