Huffington Post: For Pangolins, A Long Hard Road to Freedom

03/18/2016

This pangolin was recently rehabilitated and released in Vietnam. Photo courtesy of Save Vietnam’s Wildlife.

Pangolins are scaly anteaters about the size of a house cat. They’re presumed to be the world’s most trafficked mammal, with an estimated 100,000 plucked from the wild every year in Africa and Asia—that’s one pangolin captured every five minutes.

In China and elsewhere in Asia their meat is considered a delicacy, and their scales are cooked or pulverized to treat ills from malaria and boils to excessive nervousness—although there’s no proof of their effectiveness. (Pangolin scales are made up of keratin, the same protein in our hair and fingernails.)

Vietnam hits the trifecta in the illegal pangolin trade. It’s a source country, transit region, and destination all in one. Since 2011 authorities have confiscated roughly 1,450 live or whole pangolins and 8 metric tons of scales, according to the Environmental Investigation Agency, a London-based nonprofit that exposes environmental crimes.

Until recently it was legal in Vietnam for officials to sell seized pangolins right back into the trade. But a law that came into effect in January 2014 reclassified them as endangered, which prohibits that practice. Some criminals still do it, though—as happened in February 2015 when forest rangers in Bac Ninh province resold 42 confiscated Sunda pangolins to local restaurants.

Today, confiscated pangolins are likely to end up at the Carnivore and Pangolin Conservation Program’s rescue center, in Cuc Phuong National Park, not far from Hanoi. Since August 2014 the center, which was previously government-run, has been managed by an NGO, Save Vietnam’s Wildlife.

The caseload has been growing sharply, with 142 pangolins taken in during the past 18 months, versus 160 during the previous eight years.

Typically, pangolins arrive traumatized and in poor health. “Many are very frail, sick and injured when they come to us,” says Thai Van Nguyen, the founder and executive director of Save Vietnam’s Wildlife. “They’ve endured weeks or sometimes months of hard travel and force-feeding of corn meal to make them gain weight, which is disastrous for their health.”

Pangolins are sold by weight, so poachers often inject water under the animals’ skin or force-feed them limestone slurry—even stones!—to increase their profits. Many confiscated pangolins also have injuries from snare traps, abusive handling, or being wrenched from a tree during capture.

Rehabbing Pangolins

“Pangolins don’t cope well in captivity,” Van Nguyen says. That’s one of the reasons they’re not bred in captivity, and why you rarely see them in zoos. Van Nguyen observed that they seem to have their own personalities. “Some are very determined,” he says. “They’ll dig like crazy to get out and escape their enclosure.”

Pangolin being fed at the rescue center. Photo courtesy of Save Vietnam’s Wildlife.

They’re also susceptible to stress and have a highly specialized diet of live ants and termites. A single adult pangolin consumes roughly 70 million insects each year. New arrivals at the center typically refuse to eat artificial food, so keepers spend hours collecting live ants to encourage them to eat and speed their recovery. “Food’s a problem,” Van Nguyen says. “Getting ants is a time-consuming business.”

To get those ants, pangolin keepers use a special tool like a giant pair of scissors at the end of a 15-foot-long (5 meters) bamboo pole. They snip ant nests from trees and catch them in large plastic bags. It takes half a day to collect two bags, about 50 pounds, of ants—enough to keep 70 pangolins satisfied for one day.

“It’s hard work, especially if the weather’s hot, or it’s raining,” Van Nguyen says. “Or we might be bitten by weaver ants—they always find the softest skin to bite! But it’s all worth it when we see our pangolins eating.”

After a week or so the pangolins are transitioned to a healthy mix of silkworm larvae and ants purchased from a supplier in south Vietnam. It costs about ten dollars a week (roughly one-quarter the average monthly salary in Vietnam) to feed a single pangolin, and on top of that are the costs of medicine, veterinary care, and keepers’ wages.

It usually takes a month or longer for the pangolins’ wounds to heal and for them to regain their strength and recover from the trauma of being smuggled.

Going Home

Once they’re fit and free of disease, they’re returned to the wild. Locations are kept secret to prevent recapture, and the animals are monitored when possible.

“Vietnam is not 100 percent safe,” Van Nguyen says. “We carry out research in the field and work closely with government rangers to improve law enforcement and habitat protection.”

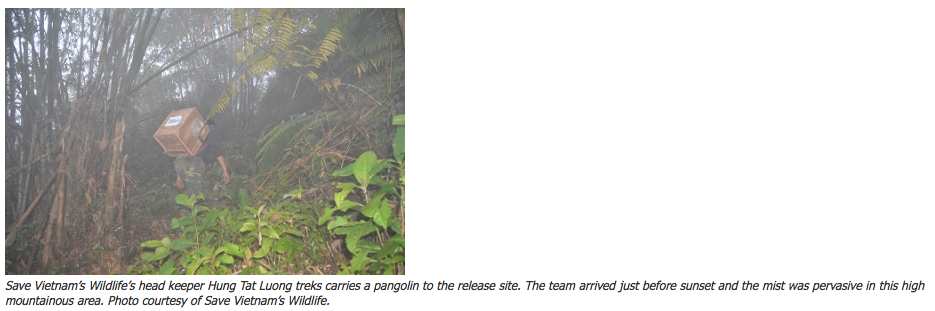

Save Vietnam’s Wildlife’s head keeper Hung Tat Luong treks carries a pangolin to the release site. The team arrived just before sunset and the mist was pervasive in this high mountainous area. Photo courtesy of Save Vietnam’s Wildlife.

During the past eight months, Save Vietnam’s Wildlife has rehabilitated and released 75 Sunda pangolins, including, on February 17, a mother and her baby and 14 others.

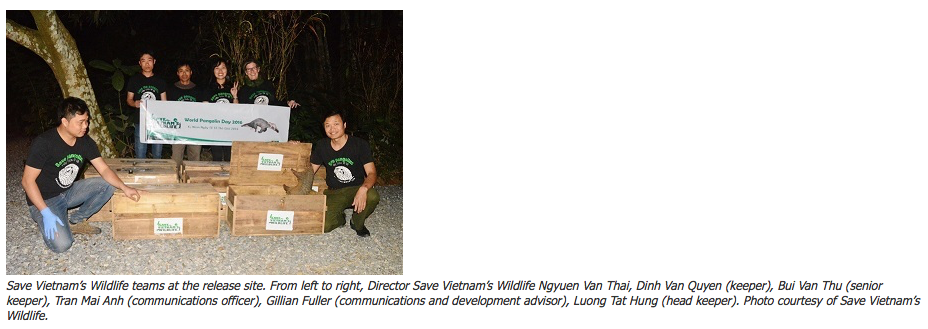

“It was incredibly exciting,” says Gillian Fuller, the organization’s communications director. “We had six of our staff, plus forestry department rangers and volunteers from WWF-Vietnam all helping.”

Save Vietnam’s Wildlife teams at the release site. From left to right, Director Save Vietnam’s Wildlife Ngyuen Van Thai, Dinh Van Quyen (keeper), Bui Van Thu (senior keeper), Tran Mai Anh (communications officer), Gillian Fuller (communications and development advisor), Luong Tat Hung (head keeper). Photo courtesy of Save Vietnam’s Wildlife.

After traveling 20 hours and 500 miles (800 kilometers) by bus to the release site, the pangolins were given a send-off meal of ants and ant eggs before being carried deep into the forest in their transfer boxes. Because they’re nocturnal, this was done at night and in good weather to ease their transition and improve their chances of survival. They’re also territorial animals, so the males and females were released alternately, roughly 350 yards apart.

“Each pangolin moves out of its box quite differently,” Fuller says. “Some shoot out, eager and enthusiastic. Others are very slow and tentative—they sniff outside and slowly progress out. But even then, it doesn’t take more than three to four minutes.”

Each release is fraught with tension and unknowns, as was the case with the mother and baby. She rolled out of the box with the baby pangolin in a protective clutch, but something startled them, and they became separated. The mother disappeared into the bush while the little one clung to a nearby tree.

Van Nguyen leaped into action. Fearing they’d be separated for good, he grabbed the baby and ran after the mother, disappearing into the dark. Fifteen minutes later, he returned with a big smile. The little family was reunited and safe in their new home—at least for now.

You can listen to Laurel’s interview with Save Vietnam’s Wildlife on her podcast, The WildLife.

Laurel Neme is a freelance writer and author of Animal Investigators: How the World’s First Wildlife Forensics Lab is Solving Crimes and Saving Endangered Species and Orangutan Houdini. Follow her on Twitter and Facebook.

This article was originally published on National Geographic under the title “Happy Ending for Smuggled Scaly Anteaters.” It is published here with permission. For full article, please click here.